About Alaskan Malamutes

Please give me credit if you copy this information onto your site

This page represents hundreds of research hours

Flattering to see the page whole on other websites, but please give credit where credit due

|

The Alaskan Malamute, one of the oldest Arctic sled dogs, was named after the native Inuit tribe called Mahlemuts, who settled along the shores of Kotzebue Sound in the upper western part of Alaska, within the Arctic Circle. Bone and ivory carvings dated to 20,000 years ago show ancient Malamutes almost identical to today's breed.

Malamutes babysat the Mahlemut children while parents were out on hunts which is one reason they make very good family pets.

Their use of dogs was a partnership for survival. In summer, the Mahlemut people fished and hunted inland. In winter, they hunted sea mammals on the coast. Dogs assisted in hauling their possessions between spots, tracking polar bears and other quarry, hunting seals, moving meat from the hunt back to their base and with the hunt itself, as well as lookouts for bears and guarding caribou herds..

Often, they neutered all male dogs except the lead dogs. This ensured that females were bred only by the best dogs. Traits were maintained by the most basic criteria - survival. The dogs that prevailed were most suited for the environment, and for the work. When the first outside explorers came to the region in the 1700s, they were impressed not only by the hardy dog but also by their owners' obvious attachment to them.

Early writings indicate that the dogs kept by the Mahlemut people were better cared for than was usual for Arctic sled dogs, and this seemingly accounts for the breed's affectionate disposition. Recent DNA analysis confirms that this is one of the oldest breeds of dog. |

Alaskan Malamute Video MPG format Visit AKC Alaskan Malamute page

|

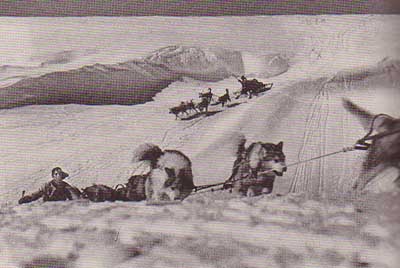

This dog was never destined to be a racing sled dog; instead, it was used for heavy freighting, pulling thousands of pounds of supplies to villages and camps. It is a heavy-boned dog, with powerfully built, strong shoulders. When working, the Malamute shows a steady, balanced, tireless gait. It is not built for speed, but for heavy draft work.

Such was the prowess of the malamute that Eskimos who lived inland traveled down the Kobuk and Noatak rivers to Kotzebue Sound to trade furs for dogs and supplies. Thus did malamutes find their way to other regions of Alaska and even to adjacent parts of the Yukon, where the gold diggers and some of the dogs that had accompanied them to the Yukon made the malamutes' acquaintance some 100 years ago. (Additional testimony to the malamutes' hegemony was the use of the word Malamute to indicate any freight-pulling dog). ("If Looks Could Thrill")

The Alaskan Malamute is the native Alaskan Arctic breed, close cousin to the Eskimo dogs of Canada, Greenland and Labrador, cousin to the Samoyed of Russia and Siberian Husky (Kolyma River Region). As a group these dogs are referred to as "Northern", "Nordic", "Spitz-type" or "Arctic" (all refer to a dog characterized by a natural, fox- or wolf-like head with erect ears; double coat with harsh, weather-proof outer coat and a dense, woolly undercoat; well-knuckled, thickly padded feet; and a tail which rises over the back to some degree). Also in this group are Japan's Akita and the smaller Shiba Inu, as are the Norwegian Elkhound and Buhund, Finland's Karellan Bear Dog, Holland's Keeshond and many others.

As with the breeds referred to above, the Alaskan Malamute is considered a "primitive" breed, in that it has been around for millennia, and not just centuries (or less), as is the case with many of today's "modern" breeds. This means the original temperament and instinctive behavior patterns remain strong in this breed accustomed to unthinkable hardship and deprivation.

There is a natural range of size in Alaskan Malamutes. Malamutes in weight are "standard" size 65-85, but can weigh up to 140lbs or more, which are considered the Gentle Giants. The "standards" were created originally by one person's modern vision of an ideal malamute (who also never bothered to go to Alaska or the Arctic) and reluctantly increased slightly upward after great political infighting within the AMCA in the 1950s. The functionality for what the dog was originally intended is more important than the size.

The Alaskan Malamute is a member of the Working Group and was first registered by the AKC (American Kennel Club) in 1935.

The Malamute is a true pack animal with the natural instinct to "lead or be led"; therefore, training must begin as early as two to three months of age, so that you lead and not the dog.

Alaskan Malamutes are fun loving dogs, and have a sense of humor. They are also incredibly independent-minded, not surprising, given their intelligence. This also strengthens the need to begin training early. Training based on rewards and encouragement, rather than force will gain optimum results. Because of their independent-mindedness, they will push every boundary as pups. Be prepared to be consistent and firm, this breed will test your will to make sure you are still the "leader" or "alpha". If they find you are not, they will assume the "alpha" role, a situation you do not want.

They tend to learn fast, and get bored easily, so they need owners who are prepared to keep them on their toes and interested in training. They won't carry on performing the same task in the way a more obedient or obsessive breed might, rather they will simply stop cooperating, or decide to do something else more amusing, if they are asked to do the same obedience exercise too often. They are often described as bright, but stubborn. Clumsy efforts to 'show them you are the alpha' tend to be met with amusement, boredom or hostility. Alaskan Malamutes do benefit from long-term training, however, they just want you to make it interesting. Training should begin while they are pups, and firm house rules should be laid down for pups, since it's easier to teach them rules while they are little. These are generally headstrong dogs, so consistency about rules you want them to follow as adults is important right from the start as stated above.

Persons who are steady enough to cope with a growing malamute will be rewarded with a lifelong companion whose devotion is boundless; but, they caution, it takes commitment and determination to get through to the often-headstrong malamute puppy, whose ancestors were created to push on through ice, sleet, snow and impossible storms. Such tasks required an inbred determination - that isn't something the malamute switches on and off at its owner's whim. You can guide a malamute in the direction you want it to go, but you can't push it there. Nor can you be heavy handed. A malamute will not tolerate abuse. If subjected to abusive treatment on a continuing basis, the most amiable youngster can become a neurotic and unpredictable adult.

The experienced malamute owner knows how quickly the average malamute understands what you are trying to teach it -- and how long it can be before the fully understanding malamute chooses to comply. When what we are asking of them, makes no "doggie logic" to them, they will take their time to comply - giving you the chance to stop being ridiculous in their minds. When they realize you aren't giving in, but are consistently asking the same thing, they will give in (be prepared to be tested months in the future on the same issue - as they need to be sure you haven't changed your mind on this "non-doggie logic" request).

Malamutes tend to be gregarious, but with humans more so than with other dogs. In general, Malamutes have never met a stranger, but greet strangers as long lost friends. Because of this friendly nature, as a rule, they do not make good guard dogs. However, their sheer size and appearance is intimidating to strangers. Because the Alaskan Malamute was developed in the Alaskan wilderness, and all members of the human group were part of the dominant pack, and all of their belongings were shared between them and unexpected strangers were welcomed with hospitality - there was no need for the Mals in the community, to guard the humans' belongings against human intruders.

Malamutes are often quiet dogs that rarely bark, but often utter a range of yips, snorts, growls, rumbles, howls, and woo-woos. Some will harmonize soulfully in concert with every siren, and others seldom or never howl. A minority of Mals do bark, there is no 100% rule.

They are also "mouthy" dogs, not in the vocal sense. As pups, they like to take your hand or arm in their mouth as part of play, just as they would another pup. You must NOT allow this, but correct from the beginning. For some Malamutes, this is quickly corrected, for others it can take months to break the instintive habit. You must NOT give up on the corrections, for while this behavior is not intended to do harm, canine teeth should not touch human flesh - especially for this strong breed, where the slightest misstep with the wrong person could lead to injury or tragedy.

Mals are generally clean and don't "smell like dogs". They tend to groom themselves feline fashion, removing dirt or mud from themselves. They "blow" their undercoats in spring and again in fall and will need daily brushing during this major shedding time so that you keep the furry "tumbleweeds" to a minimum. During the rest of the year, a weekly brushing will keep the furry tumbleweeds away.

Malamutes need something to do or they tend to develop behavioral problems, like wrecking the house, and digging up the garden and yard. Digging seems to be inbuilt, both digging holes for fun, and to lie in. You can allow them to use the spot they have selected, and just give up putting plants there, or encourage them to use a particular spot, by burying treats in their own sandpit. Some Mals are more dedicated diggers than others. Keeping their life interesting cuts down on what humans view as destructive.

They can obviously be trained as sled dogs, and for weight-pull. Mals like to accompany their owners on long walks. Alaskan Malamutes can have especially strong prey drives, and can take after cats. They were bred to be sled dogs, not to do obedience exercises, so are best suited to this, if you can work them. Mals have also shown themselves to be accomplished in Agility, Search & Rescue, and as Therapy Dogs. Remember to keep their training interesting, not repetitious or boredom will take over.

Malamutes have incredibly keen memories. They forget nothing. This is part of what made them invaluable at following trails. This means you can't make a mistake in the rules for at least the first two years of their lives. No slack until they're over two, or you just make your own job harder in molding a well-mannered Alaskan Malamute.

Alaskan Malamutes are patient with children, but should always be supervised during play (as should any dog with children).

Mals do get along with other dogs, they are social animals, when they are properly socialized with other dogs. My male Alaskan Malamute's get along together, because they are socialized - they live, play, eat and sleep together. According to Bruce Fogle, between 6 and 12 weeks of age, dogs can be socialized with any other species. There is your window, make the most of it. After that, the socialization process takes longer.

Malamutes can be a threat to livestock. "The ancestors of today's Malamute were sometimes forced to hunt, forage, and compete for food," warns one malamute rescue group. "Consequently, malamutes have a predatory streak, and, if allowed to run loose in rural areas, will reliably slaughter livestock and wild animals. In urban and suburban areas a loose malamute is a menace to cats. Swift, fearless, and powerful, malamutes have been known to catch songbirds on the wing and, if challenged, to deal harshly with other dogs ... Anyone unprepared to deal firmly and calmly with this wild streak should not own a malamute."

The hunting style of a Mal is akin to feline style. Quiet, stealthy, stalking. They can catch mice, rabbits, birds and cats - to name a few. If socialized with cats they tend to view them as part of their pack, but this may not translate to cats encountered outside.

Because they were bred to be such Herculean workers, Malamutes need daily exercise on a leash or in an enclosed area. The person who cannot provide that exercise, diversity and the firm-but-fair discipline that enables the Malamute to function best in society should look for a less demanding breed of dog.

| Color | Description |

| Black | Black guard hair with black or dark gray undercoat |

| Alaskan Seal | Black or black-tipped guard hairs with white or cream undercoat. Dog appears black at a distance, but is not a true black because of the light undercoat |

| Wolf Sable | Black or gray guard hairs with a reddish undercoat and red trimmings. Both black and red factors evident. |

| Wolf Gray | Gray guard hairs with light gray, cream or white undercoat. Dog definitely appears gray even though there may be some black hairs on the topline. No red factor evident. |

| Silver | Light gray guard hairs with white undercoat |

| Red | A definite shade of red. Either light or dark, with liver lips and nose and light eye color. No black factor evident. |

| Blue | An off-black or bluish-charcoal color. Eye color may be affected. No black factor evident. |

| White | Both guard hairs and undercoat are white. Often evidence of a mask in cream color. Only solid color allowed. |

| Shades of gold, cream, buff, brown, or reddish hues often found on legs, ears, tail, and face between white areas of the underbody and the dark color above. | |

| Cap | A cap of color covers the top of the head and the ears, usually coming to a point in the center of the forehead |

| Goggles | Dark areas under the eyes, extending sideways to the cap |

| Bar | A dark area extending from the center point of the cap down the nose. |

| Eye Shadow | Dark markings under the eyes which do not extend out to the cap. |

| Star | A small white spot in the center of the forehead |

| Blaze | A white mark extending from the center point of the cap back up the forehead. Width and length can vary. |

| Open Face | A cap covering the head with no other markings on the face. |

| Closed Face | Dark coloring covering the face with no distinct markings on the face. |

| Full Mask | Combination of cap, goggles, and bar. |

| Mask | Combination of cap and goggles. |

| Necklace | Curving band of dark color across the chest. |

| Eagle | Two bands of dark color protruding partially across the chest forming a pattern resembling the eagle emblem. |

| Collar | White band of color encircling the neck. |

| Withers Spot | White mark varying in size but centered at the withers or at the base of the neck. |

The standard has been changed with each revision to include some marking and color variations. The latest revision (1994) adds red and sable, but still does not address blues.

Blue is not addressed in the current color listing, but it also does occur. Unless they are compared in good lighting, distinguishing a blue dog from a black can be as hard as separating navy blue and black socks. However, a blue can be easily identified by inspecting the nose, lips, eye-rims, and pads. Instead of the normal black, these will be dark bluish-charcoal rather than black. Likewise, a red will have liver pigment in these areas.

Adapted from " The Alaskan Malamute: Yesterday and Today" by Barbara A. Brooks/Sherry E. WallisHere is an excellent site on Malamute Coat Color Genetics

Show judges have not yet caught up to the standard and lean toward the common colors, grays and seals. Red dogs and all white dogs have had successful show careers, but showing reds and whites can be an uphill struggle until the judges catch up with the standard.

There is a natural range of size in the breed. The desirable "standard" AMCA freighting sizes are:

Males, 25 inches at the shoulders, 85 pounds.

Females, 23 inches at the shoulders, 75 pounds.

However, size consideration should not outweigh that of type, proportion, movement, and other functional attributes.

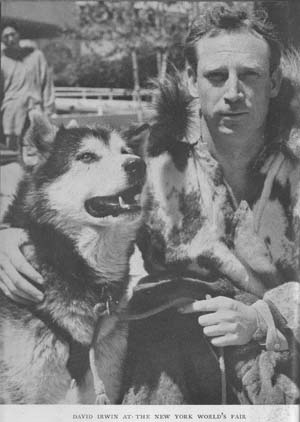

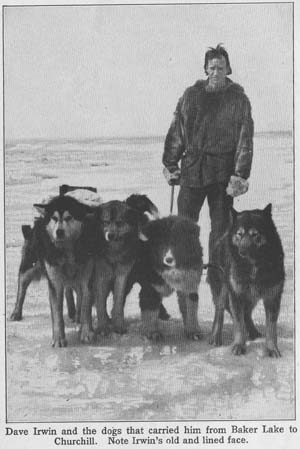

From AKC StandardDespite heavy pressure from members in the earlier years, the AMCA refused to budge on updating the standard for size and weight, possibly because of the heavy Kotzebue influence on the club. M'Loot dogs are larger than Kotzebue dogs, as are Hinman-Irwin dogs (which heavily influenced the Husky-Pak dogs). There are virtues in all three strains, and the results of crossing the strains. Today most Alaskan Malamutes are the result of mixing M'Loot with Kotzebue or Husky-Pak.

However, many foreign clubs, (UK, France and others) have desirable freighting sizes as a range of 25 to 28 inches for males, and 23 to 26 inches for females.

Interestingly, most show malamutes appear to be above the AMCA standard sizes, despite the AMCA's adherence to the standard inches & pounds in print."Despite what our standard says, I am not at all convinced that 85-lb males and 75-lb females are "the ideal freighting size". That statement was a compromise, the best we could do then, and a lot better than the way it was. But, I always felt the "original Malamute was a big dog, even after many generations of survival in a harsh environment. I think the old photos show that. In the 1950s, near Lake Placid, NY, I saw real, honest-to-God good-type Malamutes, brought out of the arctic by Jacques Suzanne, that were bigger than any real Malamutes I have seen before or since.

For many reasons I was told that anyone who ever worked sled dogs had found that big dogs "much less efficient" than the smaller ones. Some even said any dog over 80-lbs was clumsy and more likely to break down and drop out. Not being a driver, I couldn't argue. But now that opinion has been made to look silly by Will Steger and his gallant companions who journeyed totally across Antarctica in what has to be said the greatest feat of human and canine endurance ever on this earth. They accomplished with teams of 100-lb dogs - and their performance was magnificent!"

Robert ZollerAlso interesting is that Arthur Walden, who brought Malamutes and other sled dogs to New England from Alaska and the Yukon, preferred the larger dogs (120 lbs to 165 lbs) for freighting. Mr. Walden actually drove dogs in the 1890s (pre Gold rush and during), for his freighting business. He acquired his dogs from the Innuit, and learned from them. He was able to survive the harsh Arctic and maintain his freighting business because of his dogs, the only reliable transportation there.

Joe Henderson uses malamutes from 60 to 130lbs in his polar expeditions. details toward bottom of this page

Historical Tidbits

Known through out the arctic regions of the Western Hemisphere as the "husky," the original sled dog took its modern name from a slang word for "Eskimo," which in its turn is an Algonquin Indian word meaning "eater of raw flesh."The words "husky" or "eskimo dog" early on were used to refer to sled dogs and not a specific breed of sled dog in the dog fancy sense.

"Marche" was the command used by French Canadian dog drivers to their teams in the great northern wilderness. "Marche" means "march" or "get going". To the English explorers, adventurers and settlers, the word sounded like "mush". So, a dog driver then became a "musher".

Fridtjof Nansen

"To this must be added that in these regions, by intercourse with people on the Asiatic side of Bering Strait, the seafaring Eskimo may have learnt the use of the dog as a draught animal, which is an Asiatic, and not an American invention, and which is also of great importance to the whole life and distribution of the Eskimo in the ice-bound regions."

In Northern Mists: Arctic Exploration in Early Times (1911) by Fridtjof NansenIbn Ruste (circa 912 A.D.)

Ibn Ruste (circa 912 A.D.) thus says that the Rus (Scandinavians, usually Swedes) had no other occupa- tion but trading in sables, squirrel, and other furs, which they sold to anyone who would buy them.

It seems to result from what may be trustworthy in these statements that there was fairly active commercial intercourse from Bulgar with the Vesses and with the peoples on the White Sea, and perhaps in districts near the Polar Sea. A shortest night of one hour would take us to a little north of the mouth of the Dvina. In the land of the Vesses, by Lake Bielo-ozero, there was an easy way across from the Volga's tributary, Syexna, to Lake Kubenskoye, which has a connection with the Dvina ; and there was also transit to the river Onega. There was thus easy communication along the great rivers ; but besides this the traders seem also to have traveled overland with dogs; this was probably when going north to Yugria and the country of the Pechora, in the same way as traders in our time generally go there with reindeer. The trade in furs was then, as in an- tiquity, the powerful incentive ; it was that too which chiefly at- tracted the Norwegians to Bjarmeland.

In Northern Mists: Arctic Exploration in Early Times (1911) by Fridtjof NansenIbn Batuta (1302-1377)

Ibn Batuta (1302-1377) has no name for this people, any more than Abu'lfeda; but he calls their country ''the Land of Darkness/' and has an interesting description of the journey thither.

He himself, he says, wished to go there from Bulgar, but gave it ap, as little benefit was to be expected of it That land lies 40 days' journey from Biilgar, and the journey is only made in small cars drawn by dogs. For this desert has a frozen surface, upon which neither men nor horses can get foot- hold, but dogs can, as they have claws. This journey is only undertaken by rich merchants, each taking with him about a hundred carriages [sledges?], provided with sufficient food, drink and wood; for in that country there is found neither trees nor stones nor soil. As a guide through this land they have a dog which has already made the journey several times, and it is so highly prized that they pay as much as a thousand dinars [gold pieces] for one. This dog is harnessed with three others by the neck to a car [sledge?], so that it goes as the leader and the others follow it When it stops, the others do the same.

In Northern Mists: Arctic Exploration in Early Times (1911) by Fridtjof NansenMarco Polo (c. 1254 - January 8, 1324)

actual records on the use of sled dogs in the Siberian sub-arctic appear in the writings of Marco Polo in the thirteenth century.

The World of Sled Dogs by Lorna CoppingerFrancesco da Kollo 1500s

actual records on the use of sled dogs in the Siberian sub-arctic appear in the writings of Francesco da Kollo in the sixteenth century.

The World of Sled Dogs by Lorna CoppingerMartin Frobisher (c. 1535 or 1539 - 15 November 1594)

from the 1675 edition of Martin Frobisher's "Historic Navigations." This illustration shows, in the background, a dog in harness, pulling what appears to be a canoe-like sledCapt. William Edward Parry, Igloolik, 1824

The dogs of the Esquimaux, of which these people possessed above a hundred, have been so often described that there may seem little left to add respecting their external appearance, habits, and use. Our visits to Igloolik having, however, made us acquainted with some not hitherto described, I shall here offer a further account of these invaluable animals. In the form of their bodies, their short pricked ears, thick furry coat, and bushy tail, they so nearly resemble the wolf of these regions that, when a light or brindle colour, they may easily at a little distance be mistaken for that animal. To an eye accustomed to both, however, difference is perceptible in the wolf, always keeping his head down, and the tail between his legs in running whereas the dogs almost always carry their tails handsomely curled over the back.

A difference less distinguishable, when the animals are apart, is the superior size and more muscular make of the wild animal, especially about the breast and legs. The wolf is also, in general, full two inches taller than any Esquimaux dog we have seen; but those met with in 1818, in the latitude of 76 degrees, appear to come nearest to it in that respect. The tallest dog at Igloolik stood two feet one inch from the ground, measured at the withers; the average height was about two inches less than this.

The colour of the dogs varies from a white, through brindled, to black and white, or almost entirely black. Some are also of a reddish or ferruginous colour, and others have a brownish-red tinge on their legs, the rest of their bodies being of a darker colour, and these last were observed to be generally the best dogs. Their hair in the winter is from three to four inches long; but besides this, nature furnishes them during this rigorous season, with a thick undercoating of close soft wool, which they begin to cast in the spring.

While thus provided, they are able to withstand the most inclement weather without suffering from the cold, and at whatever temperature the atmosphere may be they require nothing but a shelter from the wind to make them comfortable, and even this they do not always obtain. They are also wonderfully enabled to endure the cold even on those parts of the body which are not thus protected, for we have seen a young puppy sleeping, with its bare paw laid on an iceanchor, with the thermometer at -30 degrees, which with one of our dogs would have produced immediate and intense pain, if not subsequent mortification.

They never bark, but have a long melancholy howl like that of the wolf, and this they will sometimes perform in concert for a minute or two together. They are besides always snarling and fighting among one another, by which several of them are generally lame. When much caressed and well-fed, they become quite familiar and domestic; but this mode of treatment does not improve their qualities as animals of draught. Being desirous of ascertaining whether these dogs are wolves in a state of domestication, a question which we understood to have been the subject of some speculation, Mr. Skeoch at my request made a skeleton of each, when the number of all the vertebrae was found to be the same in both, and to correspond with the well-known anatomy of the wolf.

Journal of a Second Voyage of Discovery

Capt. William Edward Parry, 1824Capt. G.F. Lyon, 1824

These useful creatures being indispensable attendants on the Eskimaux, drawing home whatever captures are made, as well as frequently carrying their masters to the chase, I know of no more proper place to introduce them, than as a part of the hunting establishment. Having myself possessed, during our second winter, a team of eleven very fine animals, I was enabled to become better acquainted with their good qualities than could possibly have been the case by the casual visits of Eskimaux to the ships.

The form of the Eskimaux dog is very similar to that of our shepherd's dogs in England, but he is more muscular and broad chested, owing to the constant and severe work to which he is brought up. His ears are pointed, and the aspect of the head is somewhat savage.

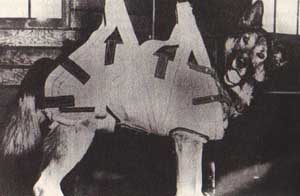

A walrus is frequently drawn along by three or four of them, and seals are sometimes carried home in the same manner, though I have, in some instances, seen a dog bring home the greater part of a seal in panniers placed across his back. This mode of conveyance is often used in the summer, and the dogs also carry skins or furniture overland to the sledges, when their masters are going on any expedition.

It might be supposed that in so cold a climate these animals had peculiar periods of gestation, like the wild creatures; but on the contrary, they bear young at every season of the year, and seldom exceed five at a litter. In December, with the thermometer 40 degrees below zero, the females were, in several instances, in heat. Cold has very little effect on these animals, for although the dogs at the huts slept within the snow passages, mine at the ships had no shelter, but lay alongside, with the thermometer at 42 degrees and 44 degrees, and with as little concern as if the weather had been mild.

I found, by several experiments, that three of my dogs could draw me on a sledge, weighing 100 pounds, at the rate of one mile in six minutes; and as a proof of the strength of a wellgrown dog, my leader drew 196 pounds singly, and to the same distance in eight minutes.

At another time seven of my dogs ran a mile in four minutes thirty seconds, drawing a heavy sledge full of men. I stopped to time them; but had I ridden they would have gone equally fast; in fact, I afterwards found that ten dogs took five minutes to go over the same space. Afterwards, in carrying stores to the Fury, one mile distant, nine dogs drew 1,611 pounds in the space of nine minutes! My sledge was on wooden runners, neither shod nor iced; had they been the latter, at least 40 pounds might have been added for every dog.

The Private Journal of Capt. G.F.Lyon, 1824Arthur Walden, Alaska & Yukon Territory, 1896-1898

"Early this winter, I made up my mind I would become a freighter, or what was called locally a 'dog-puncher'..... While everybody in this section had driven dogs more or less, there were only five of us who made this our entire business...... A dog-team with equipment for heavy freighting is totally different from that used for any other kind of dog driving. It consists of from six to seven large, heavy dogs of the native breed. We always like to have two dogs who could lead if possible, so that when breaking trail one could relieve the other."

"These dogs were locally call 'Malamutes,' from a tribe of Eskimos living at the mouth of the Yukon, from whom we got most of our dogs. The Eskimo dog, the Husky, and the Malamute are all the same breed. Variation in size is accounted for by the food they had had for generations in their particular localities.

There was another breed of dogs called the 'Porcupine River' or 'Mackenzie' Husky. These originated a great many years ago from a cross of the Eskimo with some large domesticated dog and were the best freight dogs I have ever seen, being far superior to the Eskimo and much larger and stronger. One team of these dogs, the finest I have ever seen, weighed from 145 to 165 pounds each, in working flesh.""......On the way home, one of my large Eskimo dogs, who had been following me, saw the tracks in the snow some distance ahead, but standing lower than I did he hadn't actually seen the wolf. He made a rush ahead until he got the fresh scent of the wolf, when he hustled back to me with his tail between his legs. This shows the fear of the Eskimo dog for the wild wolf."

"....It was here that I made a trip of 110 miles with my dogs without a stop. The latter part of this long trip, as the weather was warm, I slept a good part of the time on my sled. The trip was up the lakes and back again, and as the dogs had been there before and knew where they had to go, they didn't turn off on the innumerable side trails that led to men's camps along the way. They kept up a steady trot the entire distance. The journey goes to show what the Eskimo dog can do."

".....After my first attempt to find the trail myself, I turned everything over to Ribbon, and within 100 yards he picked up the trail again. These gullies kept recurring all day long, and were from 100 feet to half a mile in width, but this dog never made a mistake and always picked up the trail on the other side. When our heavily loaded teams had come over on the way out, they had not crossed directly, but had gone either up or down, so as to find an easy way up the bank. Since that time from 10 to 50 feet of snow had been blown into these gullies, so it was utterly impossible for Ribbon to smell the trail. If you ask me how he did it, I simply don't know, but he struck the trail squarely every single time and never had to find it from the side.

"This leader of mine was the first dog I had bought on the Yukon. He had come up from Norton Sound on the steamboat... so this type of country was really like home to him. He was a large black Malamute, of the old-fashioned type, and I had used him more as a leader than any other one dog. He had never gone back on me in any way.

"I lost him the next summer, when he was taken with madness over on the Inmachuk and I buried him over there with his harness on. There was an old tradition up there that a dog who is buried with his harness on will work for his master in the happy hunting grounds. I think I have a full team waiting for me. But trouble will certainly be brewing, for they were all leaders."Arthur Walden, 'A Dog Puncher on the Yukon'

Bishop Rowe, 1895-1930s

When Bishop Rowe went there in 1895, the Episcopal Church had three missions in its Alaska diocese (586,400 square miles). To reach them, he had to mush with a dog sled. From Indian and Eskimo companions, the Bishop learned to keep his socks dry at 78 below zero. He learned the knack of building a fire in a howling gale, learned to pick off wolves outside the camp circle with a rifle. Bishop Rowe mushed 2,000 miles each winter-in sum, he said, more than any other man in Alaska.

Full article on Time MagazineAlaskan Gold Rush, 1898-1906

Dog teams were the primary method of hauling freight throughout the region. Teams were hitched to sleds in winter, and to small trams on rails, to cars and even to barges (along streams) in summer. Many "outside" dogs were brought in and bred to the native Alaskan dogs.

During this period it was said that no dog larger than a spaniel was safe on the streets of Seattle, San Francisco or Los Angeles, such was the "gold fever" and need for dogs to pull sleds.Peary Arctic Club - North Pole Expeditions, 1890s to 1909

"We could certainly not have succeeded without the Eskimo dogs which furnished the traction power for our sledges, and so enabled us to carry our supplies where no other power on earth could have moved them with the requisite speed and certainty."

Commodore Robert E. Peary, 'The North Pole'"The daily ration for the dogs is one lbs of pemmican per day; but so hardy are these descendants of the artic wolves that when there is a scarcity of food they can work for a long time on very little to eat. I have, however, always endeavored so to proportion provisions to the length of time in the field, that the dogs should be at least as well fed as myself."

Commodore Robert E. Peary, 'The North Pole'

Double Team of Esquimo dogs at the North Pole

Matthew Henson"The dogs are ever interesting. They never bark, and often bite, but there is no danger from their bites. To get together a team that has not been tied down the night before is a job. You take a piece of meat, frozen as stiff as a piece of sheet-iron, in one hand, and the harness in the other, you single out the cur you are after, make proper advances, and when he comes sniffling and snuffling and all the time keeping at a safe distance, you drop the sheet-iron on the snow, the brute makes a dive, and you make a flop, you grab the nearest thing grabable - ear, leg, or bunch of hair - and do your best to catch his throat, after which, everything is easy. Slip the harness over the head, push the forepaws through, and there you are, one dog hooked up and harnessed. After licking the bites and sucking the blood, you tie said dog to a rock and start for the next one. It is only a question of time before you have your team. When you have them, leave them alone; they must now decide who is fit to be the king of the team, and so they fight, they fight and fight; and once they have decided, the king is king. A growl from him, or only a look, is enough, all obey, except the females, and the females have their way, for, true to type, the males never harm the females, and it is always the females who start the trouble.

"The dogs when not hitched to the sledges were kept together in teams and tied up, both at the ship and while we were hunting. They were not allowed to roam at large, for past experience with these customers had taught us that nothing in the way of food was safe from the attack of Esquimo dogs. I have seen tin boxes that had been chewed open by dogs in order to get at the contents, tin cans of condensed milk being gnawed like a bone, and skin clothing being chewed up like so much gravy. Dog fights were hourly occurrences, and we lost a great many by the ravages of the mysterious Arctic disease, piblokto, which affects all dog life and frequently human life. Indeed it looked for a time as if we should lose the whole pack, so rapidly did they die, but constant care and attention permitted us to save most of them, and the fittest survived.

"Next to the Esquimos, the dogs are the most interesting subjects in the Arctic regions, and I could tell lots of tales to prove their intelligence and sagacity. These animals, more wolf than dog, have associated themselves with the human beings of this country as have their kin in more congenial places of the earth. Wide head, sharp nose, and pointed ears, thick wiry hair, and, in some of the males, a heavy mane; thick bush tail, curved up over the back; deep chest and forelegs wide apart; a typical Esquimo dog is the picture of alert attention. They are as intelligent as any dog in civilization, and a thousand times more useful. They earn their own livings and disdain any of the comforts of life. Indeed it seems that when life is made pleasant for them they get sick, lie down, and die; and when out on the march, with no food for days, thin, gaunt skeletons of their former selves, they will drag at the traces of the sledges and by their uncomplaining conduct, inspire their human companions to keep on.

"Without the Esquimo dog, the story of the North Pole, would remain untold; for human ingenuity has not yet devised any other means to overcome the obstacles of cold, storm, and ice that nature has placed in the way than those that were utilized on this expedition."

Matthew Henson, 'A Negro Explorer at the North Pole'"The dogs aboard the ship were the survivors of the pack that had been with us all through the campaign, and a number of litters of puppies that had been whelped since the spring season. Our dogs were well acquainted with each other and dog fights were infrequent and of little interest, but the arrival of the first dog of the new party was the signal for the grandest dog fight I have ever witnessed. I feel justified in using the language of the fairy Ariel, in Shakespear's "Tempest"; "Now is Hell empty, and all the devils are here," "

"Backward and forward, the foredeck of the ship was a howling, snarling, biting, yelping, moving mass of fury, and it was a long round of fully ten or fifteen minutes before the two king dogs of the packs got together, and then began the battle for supremacy of the pack. It lasted for some time. It would have been useless to separate them. They would decide sooner or later, and it was better to have it over, even if one or both contestants were killed. At length the fight was ended; our old king dog, Nalegaksoah, the champion of the pack, and the laziest dog in it, was still the king. After vanquishing his opponent and receiving humble acknowledgments, King Nalegaksoah went stamping up and down before the pack and received the homage due him; the new dogs, whining and fawning and cringingly submissive, bowed down before him.

"The chief pleasure of the Esquimo dogs is fighting; two dogs, the best of friends, will hair-pull and bite each other for no cause whatever, and strange dogs fight at sight; teammates fight each other on the slightest of provocations; and it seems as though sometimes the fights are held for the purpose of educating the young. When a fight is in progress, it is the usual sight to see several mother dogs, with their litters, occupying ring-side seats. I have often wondered what chance a cat would stand against an Esquimo dog."

Matthew Henson, 'A Negro Explorer at the North Pole'"A word for the polar dogs. They are intuitive and cunning and spread out on thin ice with an understanding almost human. When the "young ice" is yielding, elastic and wavy the dogs open out like a fan and do not break through."

Matthew Henson, 'A Negro Explorer at the North Pole'Peary's planning of caches, use of trail breaking teams, sending back teams at certain points with the most tired dogs, left the freshest, fittest dogs for the final dash. It wasn't in the plan for dogs to be slaughtered and used as dogfood for other dogs, as many explorers did. Henson's descriptions are clear on that - "it's a terrible thing to kill a dog", he said. However, they did not stop the native people from their occasional tradition of killing & eating dog.

Peary & Henson's remarkable North Pole 'dash' was recreated in 2000 by Northwinds, Paul Landry & Paul Crowley. They were able to duplicate the rapid time of the 1909 expedition, the first to do so since then. " Forget skis, forget "man hauling", forget snowmobiles! Its the dogs that get you there. But only if you know what you are doing." Of their Canadian Inuit dogs they said, ""Our dogs were amazing," Landry says. "The dogs would go swimming in minus 40 and get out and shake themselves and roll in the snow and then look at you like, `OK, let's go!' "We had to put one dog on a diet two weeks before we got to the Pole because he was getting too fat. They knew how to pace themselves." Landry says he doesn't doubt that Peary made better time on his trip back to Bartlett Camp. Landry and Crowley returned to 89 degrees from the Pole, where they were picked up and flown home by airplane, and in those 100 kilometers Landry said the duo's speed increased 25 percent. "It was very easy," Landry says. "The dogs were keen and motivated and there was no route finding. The dogs were following their trail. They pee along the way and they pick up on that smell."

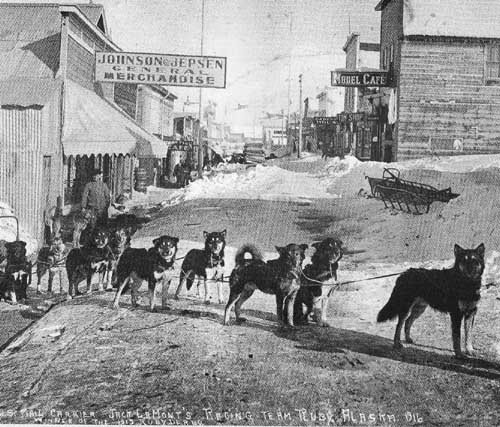

North Pole 20001890s to 1963 - Mail Carriers

Sled dogs were important to the mail service, as the only reliable transportation. So important were they, that a federal law required all other sled dog drivers to yield right-of-oway to any mail-carrying team encountered. The peak of mail service dog-teams was from around 1910 into the late 1930s. Individual drivers contracted for different mail routes. These individual drivers lost their contracts for mail service as airlines began bidding on the contracts in the late 1930s. Depending on an individual driver's route, the size of dogs and the number of dogs they used varied. Some used 110 lb plus dogs, and others preferred 90lb dogs.

In 1963, the last U.S. Postal Service mail driver, on St. Lawrence Island, retired with his dog team, replaced by an airplane. Although USPS kept him and his team on retainer, as a backup to the airplane.

Good link on dog-team mail service is DogSled Mail in the Yukon in the 1890s

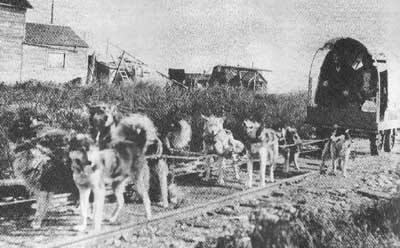

Anchorage Museum1890s to mid 1900s - Working Dogs - Miscellaneous Tasks

As the only reliable transportation during the long winter months, sled dogs were put to work in a variety of tasks.

Hauling Laundry

Anchorage Museum

Towing boats & barges

early postcard

Rail Service

on abandoned lines

The Alaska Journal

Baseball Field Maintenance

Anchorage Museum1897 - Alaskan Sled Dogs Aid Coast Guard in Rescue Mission

The fall of 1897 came early and trapped 8 whaling ships in the ice, leaving them without resupply until spring, facing starvation. The Coast Guard sent the Cutter Bear to aid. They got as close as the ice allowed and then via dog sled traveled to obtain several herds of deer to be driven to the trapped sailors, as their winter food."The powers of endurance of the Eskimo dogs are wonderful. The team I bought at St. Michaels, having already brought us that far, took me to Golofnin Bay, back again to the head of Norton Sound, and then across the country to Cape Blossom. From there it took Jarvis to Point Barrow, and finally returned with Lopp to Cape Prince of Wales, thus having traveled over 2400 miles. It had dragged heavy loads, most of the way over difficult trails, and had had only a few days' rest at odd times. Only one dog was lost out of the seven (he having been shot at Cape Smyth); the other six were in excellent condition at the end of the journey. It must be remembered, too, that when traveling through country where villages are few and far between, dog food must be carried along, and most of the time these dogs received but one meal a day, and that meal was a small one."

Lieut. Ellsworth P. Bertholf, U. S. R. C. S."In traveling we usually halted once during the day to allow the deer to feed, and again at night, at which times he paws up the snow with his hoofs, using them very skillfully, thus exposing the moss beneath. When the snow is very deep, this causes the deer much labor, so that after dragging a sled all day, and working half the night for his food, he seems to need a day of rest in each four or five, for, after all, the deer is rather a delicate animal. The dogs, on the contrary, are very tough little fellows, and will travel day after day right along if properly fed, unless their feet become badly cut by the crusty snow."

Lieut. Ellsworth P. Bertholf, U. S. R. C. S.

The survivors of the dog team that dragged the rescue party twenty-four hundred milesRoyal North-West Mounted Police (Yukon & Northwest Territories) - 1900 to 1920s

"Day in and day out, men on the trail had to deal with sled dogs. If the dogs were not kept in good shape, an entire expedition could suffer. Dogs that were used on any long patrol had to be able to survive in temperatures that dipped to -80°F, and to pull enough of a load to make it worthwhile putting them in harness in the first place. On long patrols, the Mounties normally used five-dog teams. This number could be handled relatively easily, yet get the job done.

"The sled dogs used by the Mounties were malemutes and Mackenzie River breeds. These were big animals, ranging from 80 to 150 pounds, and they often had wolf strain in them. They were willing workers and, generally speaking, of good enough nature for a driver to work them. One of their chief assets, besides stamina and ability to pull, was that their feet could stand up under snow and ice conditions better than most other breeds."

The Lost Patrol The Mounties' Yukon Tragedy by Dick NorthAlaska Telegraph Line - 1901

The future "father of the Air Force", Lt. Billy Mitchell was sent to Fort Egbert in Alaska (near Eagle) in 1901 to supervise the building of the Washington-Alaska Military Cable and Telegraph System. Hardly any work was being done. Troops had been using horses to haul equipment during the summer, but all worked ceased for the long winters. With a 5 year completion deadline, Lt. Mitchell innovatively consulted local natives and civilians. He then devised a plan to use dog teams to move equipment and supplies during the winter. He was the first military leader to purchase sled dogs and keep them year round. Following advice of the locals, he became an expert at selecting sled dogs, and acquired 200 dogs, which he kept corralled at Fort Egbert running loose in a huge pack. One of his best dogs was a 120 lb "Mackenzie River husky", Pointer. This dog saved his life after he fell through thin ice. Lead dog Pointer pulled the entire team and Mitchell free.

Lt. Mitchell used techniques acquired from native Alaskans - removing incisors; stand by with whip during feeding time to ensure no dog would steal the others' food or start a fight.

Teams of dogs and men worked to move cables, poles and other equipment. Because of this, the telegraph line was completed in 2 years - 3 years ahead of schedule!

adapted from Soldiers & Sled Dogs by Charles L. Dean1901-1904 - Swedish Antarctic Expedition

Otto Nordenskjöld a Swedish geologist, led this expedition which used sledge dogs. He had previously led an expedition to the Yukon in 1898. Subsequently he led a expedition to Greenland in 1909.1907-1914 - Ernest deKoven Leffingwell

Polar Explorer and Geologist Ernest D.K. Leffingwell mapped Alaska's Arctic coast during the years 1907-1914. He also mapped the Brooks Range, which is now part of ANWR. He was assisted by the Inupiat. He was the first to scientifically describe permafrost and to pose theories about permafrost which have largely proven true. He accurately identified the oil potential of the area. This endeavor made extensive use of sled dogs. Leffingwell spent 9 summers and 6 winters on the Arctic coast of Alaska, making 31 trips by dog sled and/or small boats.

Click here for his geological reports.

Joe Henderson and his team of 22 Alaskan Malamutes have been following Leffingwell's trails in the 2000s, traveling unsupported for up to 5 months at a time. Spend some time on Joe Henderson's site and read his excellent articles about Alaskan Malamutes and mushing.1908 Alaskan Malamute description:

"There are three broad divisions among the dogs of the North. . . The malamutes have gained the widest fame of the three, their name being so closely linked to the interior that one suggests the other. They are hereditary workers, their ancestors for hundreds of years back having toiled along the frozen trails of Alaska and the British Yukon in Indian and Eskimo teams. . . . They are 'wise' in the slang meaning of the word, it being a common saying along the . . . Yukon that a malamute is 'the most cheerful worker and the most obstinate shirk; intelligent or dense, but always cunning, crafty, and wise; stealing anything not tied down.'

These wiry sled-dogs came originally from the lower Yukon country, their name, according to the Indians, being derived from the word Malamoot, the name of an Eskimo tribe living on the Bering Sea coast, the first natives it is believed to develop the sled dog in Alaska. . . .

The typical malamute's thick gray hair, his short stout neck, sharp-pointed muzzle, the erect pointed ears, and heavy forequarters suggest the gray wolf of the Far North, while the self-reliant independence of his bearing as he stands between the traces shows his descent from a long line of toiling sled dogs. With generations of workers behind him, he makes an exceptionally strong and reliable leader, in that place displaying the cunning, wisdom and trickery that characterize his breed. No smoother or smarter leader exists. No other can make life so miserable for an inexperienced or cruel 'musher.' So observant is he that once he passes over a trail its most insignificant details seem engraved on his memory, and years later, no matter how much snow has fallen or how badly the narrow road has become drifted, he will follow it with unhesitating certainty. He will find the way and guide the team to some lonely outpost, even with the 'musher,' . . . lies half-unconscious . . ."

Mr. Jackson B. Corbett, Jr. - a reply to a Gazette article written in 1908 by Commodore Peary about the Greenland Eskimo Dogs he used on his North Pole expedition.1908 - Siberian Huskies introduced into Alaska & Yukon Territory

Sled racing became an avid sport in Alaska and the Yukon. Dogs imported from Siberia were much lighter and faster than heavy freighting dogs like Alaskan Malamutes, and became the favorites for winning races.

As race fever took hold, more Siberian Huskies were bred and fewer Alaskan Malamutes.

Some still raced Malamutes for the sheer fun, and still do.

An early Alaskan Malamute musher was Dr. Roland Lombard, a veterinarian from Wayland, MA and one of the most successfull "outsiders" to compete in Alaska dog racing. His most important contributions however, were improved dog-care practices

The Eskimo Bandits, an all Alaskan Malamute team, owned & handled by David & Betty Britz, were training to run and finish the Iditarod. No recent information can be found on their status in this venture.

In 1994, Storm Kloud Alaskan Malamutes, owned by Nancy Russell, and handled by Jamie Nelson, ran the Iditarod. Click here to see the 1994 Iditarod Malamutes.

Quinault Alaskan Malamutes owned by Twila Baker are training to run in the 2014 Iditarod. Follow their Run For The Red Lantern.

From Europe, Hendrik Stachnau, Christer Afseer and Kristin Esseth are training Team-MalamuteQuest for a run in the Yukon Quest. Like the Iditarod this is a 1000 mile race.

From my interaction with mushers on Facebook, it looks like mushers from the US, Canada, Europe, Russia and Australia participate in racing their malamutes. They're not looking to change the breed and recognize they won't often, if ever, come in first, but they finish.

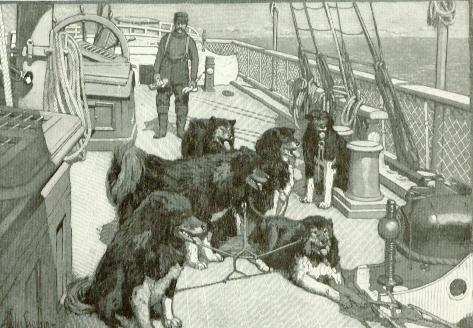

Roald Amundsen - First to Reach the South Pole - 1911-1912

Amundsen acquired 100 Greenland Eskimo dogs for his journey to the South Pole.

He followed his great compatriot's, Fridtjof Nansen, method of the combination of dogs and skis. Nansen realized the natural gait of dogs pulling a sledge matched that of a cross-country skier. While skiers prefer long, methodical efforts, dogs prefer sprints with many rests. Amundsen didn't fight nature, and went with the dogs' rhythms.

Amundsen learned to drive dogs from the Netsilik Eskimos, as well as the art of survival in cold climate. He decided to use Alaska Eskimo dog-harnesses for tandem pulling instead of the Greenland Eskimo harnesses, which he indicated cause "raw places" on the dogs.

"From the very first I tried in every way to insist upon the paramount importance to our whole enterprise of getting our draught animals successfully conveyed to our destination. If we had any watchword at this time it was: "Dogs first, and dogs all the time." "

Eskimo dogs on Amundsen's South Pole Expedition

"..they very often form friendships, which are sometimes so strong that one dog simply cannot live without the other. Before we let the dogs loose we had remarked that there were a few who.... did not seem as happy as they should have been. .... The day we let them loose we discovered what had been the matter with the ones that had moped; they had some old friend who had chanced to be placed in some other part of the deck... It was really touching to see the joy they showed on meeting again; they became quite different animals."

"..Strange beasts! what can they have meant by this howling? One began, then two, then a few more, and finally, the whole hundred. As a rule, during a concert like this they sit well down, stretch their heads as high in the air as they can, and howl to their hearts' content. During this act they seem very preoccupied, and are not easily disturbed. But the strangest thing is the way the concert comes to an end. It stops suddenly along the whole line--no stragglers, no "one cheer more." What is it that imposes this simultaneous stop? I have observed and studied it time after time without result. One would think it was a song that had been learnt. Do these animals possess a power of communicating with each other? The question is extraordinarily interesting. No one among us, who has had long acquaintance with Eskimo dogs, doubts that they have this power. I learned at last to understand their different sounds so well that I could tell by their voices what was going on without seeing them. Fighting, play, love-making, etc., each had its special sound. If they wanted to express their devotion and affection for their master, they would do it in a quite different way. If one of them was doing something wrong--something they knew they were not allowed to do, such as breaking into a meat-store, for example--the others, who could not get in, ran out and gave vent to a sound quite different from those I have mentioned. I believe most of us learned to distinguish these different sounds. There can hardly be a more interesting animal to observe, or one that offers greater variety of study, than the Eskimo dog. From his ancestor the wolf he has inherited the instinct of self-preservation -- the right of the stronger -- in a far higher degree than our domestic dog. The struggle for life has brought him to early maturity, and given him such qualities as frugality and endurance in an altogether surprising degree. His intelligence is sharp, clear and well developed for the work he is born to, and the conditions in which he is brought up. We must not call the Eskimo dog slow to learn because he cannot sit up and take sugar when he is told; these are things so widely separated from the serious business of his life that he will never be able to understand them, or only with great difficulty. Among themselves the right of the stronger is the only law. The strongest rules, and does as he pleases undisputedly; everything belongs to him. The weaker ones get the crumbs. Friendship easily springs up between these animals -- always combined with respect and fear of the stronger. The weaker, with his instinct of self-preservation, seeks the protection of the stronger. The stronger accepts the position of protector, and thereby secures a trusty helper, always with the thought of one stronger than himself. The instinct of self-preservation is to be found everywhere, and it is so, too with their relations with man. The dog has learnt to value man as his benefactor, from whom he receives everything necessary for his support. Affection and devotion seem also to have their part in these relations, but no doubt on a closer examination the instinct of self-preservation is at the root of all. As a consequence of this, his respect for his master is far greater than in our domestic dog, with whom respect only exists as a consequence of the fear of a beating. I could without hesitation take the food out of the mouth of any one of my twelve dogs; not one of them would attempt to bite me. And why? Because their respect, as a consequence of the fear of getting nothing next time, was predominant. With my dogs at home I certainly should not try the same thing. They would at once defend their food, and if necessary, they would not shrink from using their teeth; and this in spite of the fact that these dogs have to all appearance the same respect as the others. What, then is the reason? It is that this respect is not based on a serious foundation -- the instinct of self-preservation -- but simply on the fear of a hiding. A case like this proves that the foundation is too weak; the desire of food overcomes the fear of the stick, and the result is a snap."

Captain Roald Amundsen, " The South Pole"

Robert F. Scott, 1911-1913 Antarctic Expedition

On his fatal second Antarctic expedition, Scott used 33 sled dogs, only 2 of which were Esquimaux, the others mostly Siberian.

As with his 1901-1904 expedition, sleddogs were never considered by him as a primary source of transportation, and he didn't require his men to be trained in the use of dogs. It was irrelvant to Scott that those who had immense experience crossing ice (Like Nansen and Amundsen and Peary) preferred dogs over any conceivable alternative. On this second expedition he used Siberian ponies as well as dogs, and did everything in his power to help the ponies succeed, which alas they did not.

'The Voyage of the Discovery' by Captain Robert F. Scott and Scott's Last Expedition - The Journals' by Robert Falcon ScottSir Douglas Mawson - 1911-1914 Australasian Antarctic Expedition

Acquired 49 Greenland Esquimaux sledging dogs for the expedition, including "Amundsen" one of the sledge dogs sent down to him from Amundsen's South Polar Expedition. Not all the dogs survived the voyage to Anarctica. They acquired another 21 Greenland dogs presented by Captain Amundsen upon his return from his South Polar expedition"Up to this date the dogs had been kept on the chain, on account of their depredations amongst the seals and penguins. The severe weather now made it necessary to release them. Thenceforth, their abode for part of the day was inside the veranda, where a section was barricaded-off for their exclusive use. Outside in heavy drift their habit was to take up a position in the lee of some large object, such as the Hut. In such a position they were soon completely buried and oblivious to the outside elements. Thus one would sometimes tread on a dog, hidden beneath the snow; and the dog often showed less surprise than the offending man. What the dogs detested most of all during the blizzard-spells was the drift-snow filling their eyes until they were forced to stop and brush it away frantically with their paws. Other inconveniences were the icy casing which formed from the thawing snow on their thick coats, and the fact that when they lay in one position, especially on ice, for any length of time they become frozen down, and only freed themselves at the expense of tufts of hair. In high winds, accompanied by a low temperature, they were certainly very miserable, unless in some kind of shelter.

Several families were born at this time, but although we did everything possible for them they all perished, except one; the offspring of Gadget. This puppy was called "Blizzard." It was housed for a while in the veranda and, later on, in the Hangar. Needless to say, Blizzard was a great favourite and much in demand as a pet."

"Two days later another attempt was made by Ninnis and Mertz, and, in dense drift, after wandering about for a long time they happened on the Cave, to find that the dogs were not there, though spots were discovered where they had evidently been sleeping in the snow. Coming back disconsolately, they found that the dogs had reached the Hut not long before them. Apparently the two vagrants, hearing Ninnis and Mertz blundering about in the drift in search of the depot, had decided that it was time to return home. We concluded that the ways of these Greenland dogs were past finding out."

"In sledging over wide, monotonous wastes with dogs as the motive power, it is necessary to have a forerunner, that is, somebody to go ahead and point the way, otherwise the dogs will run aimlessly about. Returning over old tracks, they will pull along steadily and keep a course. In Adelie Land we had no opportunity of verifying this, as the continuous winds soon obliterated the impression of the runners.

If the weather is reasonably good and food is ample, sledging dogs enjoy their work. Their desire to pull is doubtless inborn, implanted in a long line of ancestors who have faithfully served the Esquimaux. We found that the dogs were glad to get their harnesses on and to be led away to the sledge. Really, it was often a case of the dog leading the man, for, as soon as its harness was in place, the impatient animal strained to drag whatever might be attached to the other end of the rope. Before attaching a team of dogs to a sledge, it was necessary to anchor the latter firmly, otherwise in their ardour they would make off with it before everything was ready.

There can be no question as to the value of dogs as a means of traction in the Polar regions, except when travelling continuously over very rugged country, over heavily crevassed areas, or during unusually bad weather. It is in such special stances that the superiority of man-hauling has been proved. Further, in an enterprise where human life is always at stake, it is only fair to put forward the consideration that the dogs represent a reserve of food in case of extreme emergency."

"He took to the harness once more but soon became uncertain in his footsteps, staggered along and then tottered and fell. Poor brutes! that was the way they all gave in--pulling till they dropped."

"On the 23rd Lassie, one of the dogs, was badly wounded in a fight and had to be shot. Quarrels amongst the dogs had to be quelled immediately, otherwise they would probably mean the death of some unfortunate animal which happened to be thrown down amongst the pack. Whenever a dog was down, it was the way of these brutes to attack him irrespective of whether they were friends or foes.

Among our dogs there were several groups whose members always consorted together. Thus, George and Lassie were friends and, when the latter was killed, George, who was naturally a miserable, downtrodden creature, became a kind of pariah, morose and solitary and at war with all except Peary and Fix, with whom he and Lassie had been associated in fights against the rest. The other dogs lived together in some kind of harmony, Jack and Amundsen standing out as particular chums, while the "pups," as we called them--D'Urville, Ross and Wilkes ("Monkey")--were a trio born in Adelie Land and, therefore, comrades in misfortune. Hoyle, as a pup, was treated benevolently by all the others, and entered the fellowship of the other three when he grew up. Among the rest, Mikkel stood out as a good fighter, Colonel as the biggest dog and ringleader against the Peary-Fix faction, Fram as a nervous intractable animal, and Mary as the sole representative of the sex.

It was remarkable that Peary, Fix and George in their hatred of the others, who were penned up in the dog shelter during bad weather, would absent themselves for days on a snow ramp near the Magnetograph House, where they were partly protected from the wind by rocks. George, from being a mere associate of Peary and Fix, became more amiable as the year went by, and at times it was quite pathetic to see his attempts at friendliness.

We became very fond of the dogs despite their habit of howling at night and their wolfish ferocity. They always gave one a welcome, in drift or sunshine, and though ruled by the law of force, they had a few domestic traits to make them civilized."

The Home of the Blizzard, by Douglas Mawson

1913 - present - climbing Mount McKinley

In June 1913, a four-man team led by Hudson Stuck, Episcopal Archdeacon of the Yukon, reached the 20,320-foot summit of McKinley. In mid-march the four-man expedition had used dog teams to relay one and one-half tons of food, firewood and gear 50 miles, from the north side to the base of the mountain.

Stuck's expedition then drove a team to the head of Muldrow Glacier, from where the climbers ferried loads to intermediate camps. Finally, on June 7 they left their camp at 17, 500 feet and struggled to the top.

Although dog teams have been used to support a number of expeditions, only once have dogs actually been mushed to the top of North America's highest peak. This event happened in 1979 when Joe Redington Sr. and Susan Butcher drove a team of 4 dogs to McKinley's summit. Redington called the climb "the toughest trip I ever took" and vowed he wouldn't try climbing the moutain with a dog team again. "You just can't keep up with them. They are too strong. Look at them. They look better now than when we left."

Dog teams were used in further Mount McKinley expeditions

1947 Supplying Mount McKinley expedition

Earl Norris & team crossing ice bridge

Mount McKinley Tourist Guide

Adapted from Alaska GeographicWorld War I

During this war, the French desperately needed a way to get relief supplies to their troops. Several Nome, Alaska residents left to join the French Army. One of those men was Lt. Rene Haas. Famed dog driver & racer, "Scotty" Allan, already consulted by Arctic explorers Roald Amundsen and Vihjalmur Stefansson and others, was sought out by the French government via Lt. Haas to supply dogs and sleds and to train soldiers in dog driving. After secretly transporting dogs from Alaska to Quebec by rail, he acquired additional dogs. The problem was to get the dogs across the Atlantic without tipping off German submarines of their cargo. They didn't want the dogs on deck because their noise would alert enemy subs. "Scotty" Allan trained the dogs not to sing or bark during the 2 week passage, and they were housed in shipping crates chained to the deck.

Barge carrying more than 100 sleddogs, off the coast of Nome.

The dogs were bound for France during World War I

University of Alaska Archives

Once in France, Allan trained 50 Chasseurs Alpins (French mountain soldiers) to drive the dogs. The men had to overcome the language barrier and learn to give the dogs English commands. The dogs were divided into 60 teams, with some reserved for packing, sentry or Red Cross duty. Less than 2 months after leaving Nome, dog teams with French drivers were hauling supplies and ammunition to areas that previously could not be reached. One group of these dogs delivered 90 tons of ammunition to an artillery battery in only 4 days, where it had taken up to 2 weeks for a combination of men, horses & mules to accomplish the same thing. On another mission, dogs assisted in laying over 18 miles of field telephone wire in one night, allowing a totally isolated unit to communicate with headquarters again.

Alaska sleddogs serving in France, 1918

photo appeared in NYT in 1918

When the snows melted, dogs were hitched to narrow gauge railway cars so they could continue to transport supplies and munitions.

Three Alaskan sled dogs in French service were awarded the Croix de Guerre, one of France's highest military honors, for their actions in combat. All of the dogs who worked with the Chasseurs Alpins were rewarded with a life of leisure for their heroic service to their adopted country.

The British Army (international force in northern Russia & Siberia) used Canadian dog teams with Canadiean soldier-drivers. The dogs were "usefully employed in drawing stretchers with wounded from the firing line."

The U.S. Army made no use of sled dogs during this war. They did maintain sled dogs in Alaska during and after this war as it had be proved that in Alaska's winter, dog teams were the only dependable transportation.

adapted from Soldiers & Sled Dogs by Charles L. Dean and Alaska GeographicKnud Johan Victor Rasmussen - 1921-1925

On his fifth of eight Thule expeditions, Rasmussen (born in Greenland; father Danish, mother Greenland Inuit) became the first to traverse the Northwest Passage (across Canada and Alaska to Siberia) by dogsled when he crossed the ice sheets of Viscount Melville Sound.

He was fascinated with native languages and ways of living, including the arts of sea kayaking and dogsledding. He established a base supply station in Thule, Greenland in 1910 from which he attempted to visit as many known Inuit groups as he could. During his travels he made meticulous notes and sketches, collecting an impressive amount of Inuit artifacts and compiling hundreds of Native legends and songs.

From his Thule station, Rasmussen led five expeditions from 1921 to 1924 exploring 29,000 miles of arctic North America. His famous "Great Sledge Journey" resulted in the collection and description of Inuit folktales, songs, and poetry. That effort earned him an appointment as doctor of honor at the University of Copenhagen.The 1925 Serum Run to Nome

The last driver to arrive in Nome was Gunnar Kassen. His lead dog, Balto (owned by Leonhard Seppala), was a sturdy little Malamute. Seppala with his other team, lead by a 12 year old Siberian Husky (Togo) did the bulk of the work, but Balto got the bulk of the fame and a statue in Central Park. Photos of Balto below:

BAE I - First Byrd Antarctic Expedition - 1928-1930

"Arthur Walden, the sturdy old New Englander who would be in charge of all the sledge dogs, likewise had a long polar pedigree; he had driven huskies in Jack London's Yukon."

'Little America - Town at the End of the World' by Paul A. Carter

"Our surface transport was more in keeping with Antarctic traditions. Our dogs were mostly Greenland huskies, of the breed and blood with which some of the greatest marches in the polar regions have been made. Seventy-nine of these came from Labrador, and were donated by Frank W. Clark, of the Clark Trading Company. Sixteen dogs came from the farm of Arthur T. Walden, at Wonalancet, among them the famous "Chinook." These were heavy draught animals, of his own breed, with a splendid record in transport."

"The love these Eskimo dogs have for their work is quite wonderful."

"Had it not been for the dogs, our attempts to conquer the Antarctic by air must have ended in failure. On January 17th, Walden's single team of thirteen dogs moved 3,500 pounds of supplies from ship to base, a distance of 16 miles each trip, in two journeys. Walden's team was the backbone of our transport. Seeing him rush his heavy loads along the trail, outstripping the younger men, it was difficult to believe that he was an old man. He was 58 years old, but he had the determination and strength of youth."

Proper preparation was absolutely essential, for the reason that none of the men who would compose the two parties, with the exception of Mr. Walden, had had any previous experience in long-distance sledging. Walden was a veteran dog musher of the old school, and had had a great deal of experience hauling freight in Alaska."

"I cannot speak too highly of the dog drivers -- Walden, Goodale, Crockett, Vaughan, Bursey and Blackburn. It is they who have borne the burden of transport from the beginning;"

"There were some excellent dogs among them..... and Vaughan's leader, Dinty, a black malamute with soulful eyes and the disposition of Puck."

"Descending the farther side of the ridge, we came to a deep, but narrow crevasse, which investigation showed was a thinly bridged at the point where we proposed to cross it. Under ordinary circumstances, I confess, I should not care to try to rush a sledge across it; but these were not ordinary circumstances. Walden was of the opinion the sledges were long enough, however, to distribute the load without greater danger, and we trusted on momentum to lessen the strain.

"The first sledge cleared the crevasse in a flurry of snow- but none too quickly, at that. As the front end rose slightly on the distant side, the rear runners dipped down and broke a hole through. One by one, three other sledges made the rush without mishap. Walden, who brought up the rear guard had the heaviest sledge of all. Just as he cleared the edge, the sledge veered violently and tipped over, pinning him underneath. He fell on the brink of a drop into a second crevasse, saving himself by clutching hold of the sledge. Without a word, he scrambled clear, righted the sledge, started the dogs and resumed his steady trot."

"Eskimo dogs remain individualists to the last. They may dwell in the peaceful affinity of brothers for days on end; but for the favor of a lady or a hunk of frozen seal meat they will enthusiastically rend one another limb from limb"

Richard E. Byrd - Little America

From the Byrd Polar Archives

Only 5 sled dogs on BAE I were of Alaskan origin (Terra (60#), Nova (63#), Mutt (70#), Dinny (65#), and Coyote (65#)) - from the inventoried dogs on the expedition. These dogs were brought to Walden's Chinook kennels from Alaska by Scotty Allan along with 45 other Alaskan sled dogs (that did not go on the expedition and were to be part of Walden's compensation for the expedition).

16 sled dogs were Arthur Walden's Chinooks, including 'Old Chinook' himself.

79 sled dogs came from Labrador, and were donated by Frank W. Clark, of the Clark Trading Company. These dogs were Labrador Eskimo dogs, known at the time as Labrador Huskies. Included with these Labrador Eskimo dogs was Rowdy (77# - from the inventoried dogs on the expedition) of supposed early Alaskan Malamute fame according to Eva B. Seeley.

After the expedition, Norman Vaughan took possession of the Labrador Huskies and split them with Ed Goodale. They each setup a tourist business for people to see the dogs that went on the expedition. Vaughan got out of it shortly after and gave the remaining dogs to Ed Goodale. When Ed Goodale got out of it, the Labrador Huskies (including the famous Rowdy) went to the Seeleys who had taken over Chinook Kennels from Arthur Walden while he was out of the country (including his 45 Alaskan 'compensation' dogs).

Arthur Treadwell Walden

Walden was a writer ('A Dog Puncher on the Yukon'), an explorer, a dog driver, sled dog racer and breeder. Walden got involved with Malamutes (his best lead dog, Ribbon, was a large black Malamute) while living in Yukon Territory as a respected sledge driver in the dog-freighting business. While freighting, he was the first to break the news of the Klondike gold strike. One of his lead dogs, Hootchinoo, 3/4 wolf, and well known in the territory is believed to be the 'original' for Jack London's 'White Fang'.

After returning to the Yukon after an extended visit home to New Hampshire, he found that the Gold Rush has changed things dramatically, and not to his liking.

He eventually returned to New Hampshire, bringing the world of sled dogs with him. He brought in northern dogs, as well as St. Bernard mixes. From his St. Bernard mixes and a descendant from Admiral Peary's lead dog Polaris, he had the beginnings of what became the Chinook breed (named after one of the pups who became famous with his Antarctica exploits). He also named his Chinook Kennels at Wonalancet Farm after him. He bred Chinook to a number of bitches, including German Shepherds and kept the pups that most resembled Chinook.

He is also known for both bringing sled dogs and sled dog racing to New England, and for the founding of the New England Sled Dog Club in 1924. The NESDC is the oldest continuous U.S. sled dog club and has held sled dog races since 1924, except for a brief span during World War II.

Walden introduced sled dogs to Eva Seeley and her husband Milton while they were vacationing in New Hampshire. They loved the dogs and visited often. Several years later when he heard of Milton Seeley's poor health, he persuaded the couple to move to Wonalancet to help with the kennels while he was in Antarctica on the Byrd Expedition. They took him up on his kind offer.

To assist in the Byrd Expedition to Antarctica, Walden prepared his own teams and collected & trained sled dogs from all over that arrived with drivers by train and truck. Scotty Allan arrived from Alaska with 50 dogs (only 5 of whom went on the expedition). Walden's Chinook Kennels became the staging area for dog preparations for the Byrd Expedition, with the exception of the 79 Labrador Eskimo dogs, donated by Frank Clarke, reported by the New York Times as going straight from Montreal to Norfolk, VA by rail.